Material irregularities

Current status of MIs

The audit outcomes and the insights from our audits as detailed in this report reflect the concerning state of financial and performance management in national and provincial government. Our audits have for many years highlighted that not only are irregularities and their resultant impact not prevented from happening, such instances are also not appropriately dealt with when they are identified.

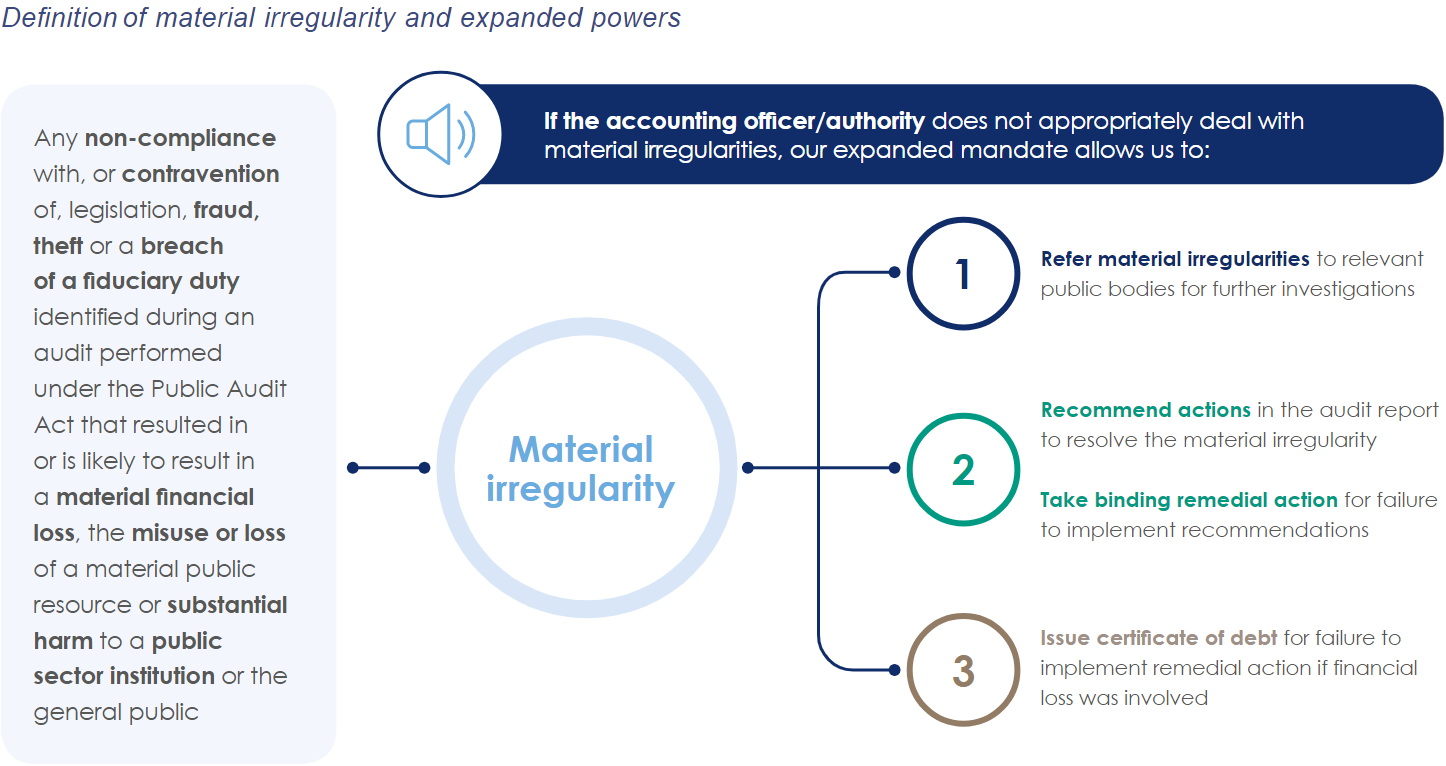

This led to amendments to the Public Audit Act, which came into effect on 1 April 2019 and gave us the mandate to report material irregularities (MIs) and to take action if accounting officers and authorities do not deal with them appropriately.

The amendments established a complementary enforcement mechanism to strengthen public sector financial and performance management so that irregularities such as non-compliance, fraud, theft and breaches of fiduciary duties and its resultant impact can be prevented, or can be dealt with appropriately.

The overall aim of our expanded mandate is to:

- promote better accountability

- improve the protection of resources

- enhance public sector performance and encourage an ethical culture

- ultimately, strengthen public sector institutions to better serve the people of South Africa.

We issue notifications of MIs to accounting officers and authorities to allow them to correct deficiencies, protect public finances and enhance the performance of auditees. By safeguarding and recovering resources, money saved or recovered can be redirected towards delivering much-needed services to South Africans.

Our expanded mandate did not change the role and responsibilities of accounting officers and authorities or the oversight and monitoring roles of executive authorities and oversight structures to prevent and deal with irregularities. Through the MI process, we complement the role and efforts of other roleplayers in the accountability ecosystem.

In this fourth year of carrying out our enforcement mandate in national and provincial government, we expanded our work significantly by implementing the process at 202 auditees – from 95 in 2020-21. We plan to further increase this number to 430 in 2022-23.

Download our latest material irregularity (MI) report

In this report, we share details on material irregularities identified across all spheres of government and their status at 30 September 2022. The report also includes information on the actions being taken to resolve the MIs – by the accounting officer or authority, or through the use of our expanded powers.

Impact of material irregularity process

There has been a shift at departments and public entities: from a slow response to our findings and recommendations over the years to attention now being paid to what we report as MIs and actions being taken to resolve these.

We found that until we issued notifications, no actions were being taken to address 82% of these matters.

An MI is resolved if all steps have been taken to recover financial losses or to recover from substantial harm, when further losses and harm are prevented through strengthening internal controls, when there are consequences for the transgressions (which include disciplinary processes) and, if applicable, the matter has been handed over to a law-enforcement agency.

Where accounting officers and authorities respond to our notifications with commitment and workable plans to implement appropriate action to resolve the MI, the intended impact of the Public Audit Act amendments is achieved – the objective was to enable corrective action to resolve MIs and prevent similar ones in future.

Such impact is evident from the actions taken by the accounting officers and authorities to resolve the MIs that resulted in (or are likely to result in) financial loss.

Below are examples of the impact achieved through the MIs that have been fully resolved and those that are in the process of being resolved. These actions were taken by the accounting officers and authorities in response to the MI notifications.

Examples of impact achieved

- Financial loss recovered: The KwaZulu-Natal Department of Health procured sanitiser detergent during the covid-19 pandemic at prices significantly higher than prescribed by the National Treasury at that time, resulting in a R1,3 million financial loss. The Special Investigating Unit investigated the matter and an acknowledgement of debt was signed with the supplier, resulting in R0,5 million of the loss already having been recovered.

- Financial loss recovered: The Pietersburg Hospital leased radiology equipment which was not used, resulting in an estimated loss of R3,7 million. The rooms in which the equipment had been installed were not accessible due to environmental safety concerns. To recover from the financial loss, the accounting officer of the Limpopo Department of Health renegotiated an extension of the contract, which allowed the equipment to be used for a further 12 months at no additional cost.

- Financial loss recovered: The Property Management Trading Entity made payments to a landlord for leasing properties in excess of the amount payable per the lease agreement, resulting in an estimated R11 million in overpayments. By 31 March 2022, R9,7 million had been recovered from the landlord and the remaining amount was in the process of being recovered.

- Financial loss in the process of recovery: The prices paid by the Department of Public Works and Infrastructure for three state events were higher than what had been approved during the quotation process. In response to the recommendations we made, the matter was handed over to the State Attorney for recovery of the R0,83 million overpaid to the supplier.

- Prevented financial loss, supplier contracts cancelled and disciplinary steps taken: The Eastern Cape Department of Human Settlements awarded three contracts for housing units to bidders that did not score the highest points in the evaluation process, resulting in higher prices being paid, as the cost of units from the appointed bidders was higher than that of the bidders scoring the highest points. On an application by the accounting officer, the High Court set aside two of the contracts, declaring them to be invalid, which prevented an estimated financial loss of R6,45 million. The accounting officer also took disciplinary steps against the officials found responsible for the non-compliance – the members of the bid adjudication committee were given a written warning for their part and the chief financial officer was dismissed (other charges were also taken into account for the dismissal).

- Prevented financial loss: The Gauteng Department of Human Settlements entered into a month-to-month contract amounting to R1,46 million per month from April 2016 for the leasing of temporary residential units instead of going with the cheaper option of purchasing them. The accounting officer cancelled the lease agreement in January 2022 and purchased the temporary residential units in June 2022.

- Prevented financial loss: The Department of Defence imported an unregistered drug (Heberon) at a cost of approximately R260 million without approval from the South African Health Products Regulatory Authority. The unused vials were repatriated to Cuba, preventing an estimated financial loss of R227 million.

- Prevented financial loss: The North West Department of Health wrote off R65,64 million in patient debt without taking reasonable steps to recover the debt and first applying the requirements of its revenue and debt management policy. The accounting officer reversed the write-off, allowing for a proper process to be followed to collect the debt.

- Disciplinary processes underway: Multiple instances of non-compliance in the procurement process for locomotives in July 2012 by the Passenger Rail Agency of South Africa resulted in the contract being unfairly awarded. In response to the remedial action we instituted against the agency to implement consequence management, investigations were completed. Seven officials were charged with procurement irregularities and they are being subjected to disciplinary processes; so far, one official has been dismissed and another has resigned.

- Fraud/criminal investigations instituted: The Department of Cooperative Governance made payments to non-qualifying government employees as part of the Community Work Programme due to ineffective internal controls for approving and processing payments. In response to the recommendations we made and an internal investigation into the matter, the accounting officer referred the matter to the Directorate for Priority Crime Investigation (the Hawks) for investigation.

- Internal controls improved: The KwaZulu-Natal Department of Health awarded contracts for radiology equipment to suppliers that did not score the highest points in the evaluation process without predefined, objective criteria for such deviation. To prevent a recurrence, the department updated its standard operating procedures and bid documents for supply chain management to address the application of objective criteria; and officials attended refresher training on supply chain management prescripts.

- Internal controls improved: The Mpumalanga Economic Growth Agency impaired debts by R292,21 million without following all the required actions provided for in its debt management policy. The accounting authority capacitated the credit control unit to enable improved debt collection by appointing legal interns, a panel of legal practitioners and an external debt collector.

- Internal controls improved: The Western Cape Department of Human Settlements did not correctly apply the evaluation criteria in the National Housing Code, resulting in beneficiaries receiving subsidies they were not entitled to and valid beneficiaries being overpaid. The accounting officer implemented an additional review by the department’s internal control function before any subsidies are approved.

Nature and status of material irregularities

By 31 August 2022 (which was the cut-off date for MIs to be included in this report), we had identified 179 MIs. We estimate the total financial loss of these MIs to be

R12 billion.

We have highlighted all of these areas of vulnerability for a number of years, including in previous general reports and the special reports we tabled on the management of government’s covid-19 and flood-relief initiatives.

These are not complex matters, but the basic disciplines and processes that should be in place at auditees to:

- procure at the best price

- pay only for what was received

- make payments on time to avoid unnecessary interest or penalties

- recover revenue owed to the state

- safeguard assets

- effectively and efficiently use the resources of the state to derive value from the money spent

- prevent fraud

- comply with legislation.

Financial losses mean that there is less money available to deliver much-needed services to South Africans and for government to achieve its strategic priorities. In addition, some of the MIs had a direct impact on the ability of auditees to deliver on projects and services.

Thirteen of the identified 179 MIs were resolved in prior years, bringing us to 166 active MIs. We only recently notified accounting officers and authorities of eight of these; and by 30 September 2022, their responses were not yet due. At that date, we were also still evaluating the responses to 34 of the newly identified MIs. This means we have evaluated and can report on the status of 124 MIs.

We provided examples of the resolved MIs earlier in the section.

Appropriate action means that we have assessed the steps being taken to resolve the MI and are comfortable that these, when fully implemented, will result in the MI having been resolved.

Different MIs need different actions (and sometimes a combination of actions) for them to be resolved. Some require financial losses to be recovered while others also require further financial losses to be prevented. Some require consequences against responsible officials and others also require fraud or criminal investigations and reporting the outcome of such investigations to the South African Police Service.

Some MIs can be resolved within a short period, while others require auditees to correct deep-rooted issues or to quantify multiple years of financial loss – which will necessarily take longer to address. For example, we issued MIs on overpayments by the National Student Financial Aid Scheme to students and tertiary institutions. To identify and quantify the full extent of the financial loss, requires the scheme to interrogate hundreds of thousands of student records and to reconcile data from 76 institutions for four academic cycles.

The average ‘age’ of the 91 MIs where appropriate action is being taken to resolve the MI, is 19 months from date of notification. The ageing of MIs is influenced by delays in implementing the necessary action. Where we assessed such delays to be reasonable, we did not invoke our powers. However, the delayed resolution of MIs highlights challenges in national and provincial government, some of which we describe below.

A common reason for delayed resolution is prolonged investigations or delays by public bodies, which hamper timeous financial loss recoveries, consequence management processes and criminal proceedings.

Examples of prolonged investigations and delays

- The North West Department of Community Safety and Transport Management spent R203 million on a contract to introduce scheduled flights to the Mahikeng and Pilanesberg airports, without any services being delivered by the suppliers. Two criminal cases were opened, one with the South African Police Service in 2017 and one with the Hawks in May 2020. The Judicial Commission of Inquiry into Allegations of State Capture, Corruption and Fraud in the Public Sector including Organs of State (Zondo Commission) raised a concern during its hearings in 2019 about the lack of progress on these matters. The MI was issued in February 2020. Four suspects have since been charged. The department also approached the National Treasury in September 2019 to investigate the matter. The external forensic investigation commissioned by the National Treasury in October 2019 is still ongoing.

- The Gauteng Department of Health awarded a contract for information technology infrastructure in March 2015 without inviting competitive bids, resulting in a financial loss of R148,9 million, as cheaper alternatives were available. Based on the outcome of a departmental investigation, the accounting officer referred the matter in July 2019 to the National Prosecuting Authority for possible criminal charges and the State Attorney for civil claims against the implicated officials. Limited progress has been made since then.

- The Department of Basic Education distributed learner materials to volunteer educators for learners who did not qualify for the Kha Ri Gude literacy programme. After a departmental investigation, the matter was referred to the Hawks in May 2017 – the investigation is still ongoing.

The speedy recovery of lost funds is often hampered by suppliers being liquidated or the loss-recovery processes of the State Attorney taking a long time to complete.

Examples of liquidation and loss-recovery delays

- In 2014 and 2018, the South African Social Security Agency made payments to a service provider for services not delivered. The service provider is currently under liquidation, making it unlikely that the total financial loss of R391,2 million will be recovered. The slow finalisation of the liquidation process also delays any processes of recovering the remaining losses from liable officials.

- During the evaluation process for a contract to service, repair and maintain equipment at health facilities, the North West Department of Health incorrectly disqualified a supplier, which resulted in higher prices being paid for the services. The official identified through an investigation to be responsible for the financial loss resigned. The accounting officer handed the matter over to the State Attorney in August 2021 for civil recovery from the official. By July 2022, no progress had been made and the accounting officer consequently withdrew the mandate from the State Attorney and appointed a legal firm to commence with recovery on behalf of the department.

Instability continues to have an impact on resolving MIs. After we have issued an MI notification, we often have to reissue the notification, or the progress of resolving the MI comes to a halt, if the original accounting officer or authority changes.

Example of instability

We notified the board of the Passenger Rail Agency of South Africa of nine MIs in 2019. The resolution of these MIs has shown little progress over the past three years as the entity has been plagued with instability at both board and key management level. After the board was disbanded, the High Court set aside the appointment of an administrator. An accounting authority functionary was then appointed as well as a new board in October 2020 to return some level of stability to the entity. The instability at chief executive level continued throughout this period though, with the last appointee being removed from office and the position currently being filled in an acting capacity.

The area in which we often see delays is in disciplining officials responsible for MIs. Either the investigation to identify the responsible officials takes too long or the disciplinary processes against implicated officials are delayed. We have also identified stumbling blocks in the disciplinary processes caused by complexities in accountability arrangements as defined in legislation.

Examples of delays in disciplinary processes

- Four of the MIs at the Department of Defence are not being resolved as the Defence Act does not provide for the defence secretary (who is the accounting officer of the department) to take disciplinary steps against military officials, as they fall under the command of the chief of the defence force. Based on the defence secretary’s investigations, she referred the matters to the chief of the defence force to deal with, but the chief did not take any action or the military board of inquiry found that the military officials should not be held accountable. For some of the MIs, the defence secretary also did not take action against the civilian officials.

- After we issued two MIs to the Property Management Trading Entity relating to the Beitbridge border post infrastructure project, the accounting officer initiated disciplinary action against the implicated officials. The State Attorney handled the case. The first hearing scheduled for April 2021 was postponed due to the legal representative of one of the officials not attending, pending a court application for reviewing the investigations report, the directive issued by the minister, and the disciplinary enquiry. A second hearing for the senior official implicated was subsequently scheduled for May 2021, during which the chairperson ruled that the court application had a bearing on the disciplinary action. The disciplinary proceedings against the three senior managers were postponed indefinitely, pending the outcome of the judicial review.

Using our expanded mandate

We are fully committed to implementing the enhanced powers given to our office – without fear, favour or prejudice. If accounting officers and authorities, supported by their political leadership, fulfil their legislated responsibilities and commit to taking swift action when we notify them of an MI, there is no need for us to use our remedial and referral powers. Yet, we do not hesitate to use these powers when accounting officers or authorities do not deal with MIs with the required seriousness.

In 19 cases where accounting officers and authorities did not appropriately address the MIs we reported to them, we used our expanded mandate by including recommendations in the audit reports or the auditor-general invoked her additional powers of referral and remedial action. The departments and public entities where we took further action (as depicted below), are also where we typically experience a slow response to our findings and to improving the control environment.

The circumstances of a referral we made in the past year are included as an example below.

Example of referral made

The National Treasury paid for software licences and annual technical support and maintenance for the Integrated Financial Management System, which was not operational. Care was not taken to ensure that the expenditure incurred was aligned to the implementation of the project.

The auditor-general approved the referral of the MI to the Special Investigating Unit in January 2022 for further investigation. The matter forms part of an investigation currently underway, in terms of a proclamation issued by the President.

The recommendations we include in the audit reports are not the normal recommendations we provide as part of our audits but instead deal with the actions accounting officers and authorities should take to resolve a specific MI. It typically deals with the following:

- Recovery: Steps to be taken to recover financial and public resource losses or to recover from harm.

- Prevention: Steps to be taken to strengthen internal controls to prevent further losses and harm.

- Consequences: Steps to be taken to effect consequences for the transgressions, including disciplinary processes and, if applicable, handing over the matter to a law-enforcement agency.

We included recommendations on eight MIs in the audit reports of six auditees. Examples of recommendations included in the 2021-22 audit reports, summarised for this report, follow.

Examples of recommendations included in audit reports

The South African Social Security Agency paid covid-19 social relief of distress grants to ineligible individuals due to inadequate internal controls to perform validations and prevent such payments.

Appropriate actions were not taken to resolve the MI. We notified the accounting officer of the following recommendations, which should be implemented by January 2023:

- Implement internal controls to prevent and detect payments to ineligible beneficiaries.

- Recover payments made to ineligible beneficiaries who were working for the state at the time of applying for the grant.

- Make an informed decision on the process, feasibility and cost effectiveness of recovering money paid to ineligible beneficiaries not employed by the state; and implement decision.

The Property Management Trading Entity did not appropriately safeguard boilers at Leeuwkop Prison during construction, resulting in them being damaged due to exposure to severe weather conditions.

Appropriate actions were not taken to resolve the MI. We notified the accounting officer of the following recommendations, which should be implemented by January 2023:

- Perform an investigation to determine if any official(s) should be held responsible and initiate disciplinary steps against the official(s).

- Quantify the financial loss and determine if the responsible official(s) are liable by law for losses suffered.

- Implement preventative mechanisms to eliminate further damage and losses as a result of inadequate safeguarding of construction site assets.

If our recommendations are not implemented, we issue remedial actions that cover the same areas of recovery, prevention and consequences. Remedial action is a binding instruction issued by the auditor-general. If the MI caused a financial loss for the state, the remedial action also includes a directive for the financial loss to be quantified and recovered.

The circumstances of one remedial action we issued are included as an example below.

Example of remedial action issued

The Free State Development Corporation appointed a service provider for electricity billing and collection services, but then did not ensure that all revenue collected was paid over to the corporation. The service provider was placed under voluntary liquidation from May 2020. By March 2021, the service provider owed the corporation R109 million.

The matter was referred to the Hawks for investigation on 15 November 2021, and is still ongoing.

The accounting authority failed to make progress with the recommendations on consequences we issued for implementation by January 2022, namely to determine whether any official(s) should be held responsible and to take the necessary disciplinary steps. The auditor-general issued remedial action to ensure that consequences are effected as recommended. We gave the accounting authority until 30 November 2022 to fully implement the remedial action.

If a directive was issued for the financial loss to be quantified and recovered and it is not implemented by the stipulated date, we can move towards the certificate of debt stage. The MIs currently in the remedial action stage do not qualify to be considered for a certificate of debt.

A culture of responsiveness, consequence management, good governance and accountability should be a shared vision for all involved, including executive authorities, Parliament and legislatures, and coordinating institutions. We urge them to also play their designated roles in the accountability ecosystem by supporting, monitoring and overseeing the much-needed improvement in – and resolution of – MIs.

When the auditor-general’s powers of referral and remedial action (and the issuing of certificates of debt in future) are invoked, it not only reflects poorly on the accounting officer or authority, but also means that other roleplayers in the accountability ecosystem have failed to act in accordance with their given responsibilities.

Other pages in this section:

Other pages in this section: