State of national and provincial government

Pressure on the fiscus

There are many challenges on the road ahead for South Africa to return to the necessary growth path. While the country embarks on economic recovery and fiscal sustainability measures following the effects of the covid-19 pandemic, the July 2021 unrest and the devastating April 2022 floods in KwaZulu-Natal and the Eastern Cape, the path ahead is still riddled with many obstacles, and balancing the fiscal challenges is a daunting task. The pressure on the fiscus is not making it easy to promptly roll out the vast planned economic reforms. Unless government successfully manages these pressures by making impactful decisions, South Africa will find itself in an untenable fiscal position.

Download our special reports on government’s covid-19 initiatives and flood-relief funds

Accounting officers and authorities managed an estimated expenditure budget of R2,58 trillion in 2021-22. At a time when departments and public entities need to do more with less, and the public’s demands for service delivery and accountability are increasing, accounting officers and authorities should do everything in their power to get the most value from every rand spent and to manage every aspect of their finances with diligence and care.

As detailed in the rest of this section, however, we are seeing a lack of prudence in spending and government practices that erode the limited funds available. This is caused by inadequate financial management and limited accountability for financial performance.

Lack of prudence in spending limited funds

Over the three-year term of the current administration, auditees have disclosed fruitless and wasteful expenditure totalling R5,83 billion.

Since 2019, we have also identified non-compliance and fraud resulting in an estimated R12 billion in financial loss through our material irregularity process. The main reasons that money is being lost include:

- poor payment practices to suppliers of goods and services

- unfair or uncompetitive procurement practices when procuring goods and services

- no or limited benefits received for money spent and properties owned

- infrastructure not maintained and secured

- uneconomical practices for leasing properties

- inadequate needs analysis and project management.

Poor payment practices

Contracts that have been awarded to suppliers must be actively managed to ensure that the suppliers deliver at the right time, price and quality before any payments are made. Payments must also be made on time to avoid interest and penalties.

Such requirements are not only standard financial management practices, they are also included in the Public Finance Management Act, which makes accounting officers and authorities responsible for ensuring that the required processes and controls are implemented.

At some auditees, poor payment practices such as late payments, overpayments and payments for goods not received resulted in (or are likely to result in) financial losses. It is common for government to have to pay interest incurred due to late payments, such as when auditees do not pay their creditors within 30 days. We have notified the accounting officers and authorities of these material irregularities.

Examples of interest paid due to late payments

- The Department of Basic Education did not pay a contractor within the required 30 days for a construction project in the Eastern Cape, resulting in interest charges of R7 million.

- The Department of Correctional Services did not make payments to a supplier as instructed by a court judgment, resulting in interest of R1,18 million.

Examples of payments made for goods and services not received

- The National Skills Fund entered into a project-funding agreement with an academy for a learnership programme. The fund approved and paid R3,19 million for three credits of ‘additional modules’ that had already been included in the original modules.

- The State Information Technology Agency entered into a contract with a service provider for assistance with a stakeholder engagement event. In April 2019, the agency made an advance payment of R1,5 million to the supplier. No services were received for the money spent.

- In 2018-19, the Department of Water and Sanitation paid a consulting firm R17,9 million for financial management services without evidence that work had been done.

- In 2020-21, the KwaZulu-Natal Department of Education did not promptly remove ex-employee from the human resource and payroll systems. As a result, the department approved and processed salary payments of R142,49 million to people it no longer employed.

Examples of overpayments

- The North West Department of Human Settlements overpaid a supplier appointed to provide project management services by R2,98 million because it did not have appropriate internal controls.

- In November 2013, the Northern Cape Department of Health entered into a radiology services contract that was extended multiple times. The contract contained a mathematical error that resulted in overpayments estimated at more than R4 million.

- Between May 2018 and December 2018, the Department of Public Works and Infrastructure spent more than the contract amount on state funerals, and the services paid for differed from those provided for in the contracts. We estimate the likely financial loss to be R9,1 million.

Unfair or uncompetitive procurement practices

Fair and competitive procurement processes enable auditees to get the best value for the limited funds available and give suppliers fair and equitable access to government business. Unfair or uncompetitive procurement processes result in auditees paying higher prices or appointing suppliers that do not deliver.

At some auditees, unfair or uncompetitive procurement practices resulted in (or are likely to result in) financial losses, as goods and services could have been obtained at a lower price. We notified the accounting officers and authorities of these material irregularities.

Examples of higher prices paid

- In July 2019, Transnet advertised a tender for the leasing of equipment. The contract was not awarded to bidders that scored the highest points, resulting in a likely loss of R29,4 million.

- In July 2019, the Department of Defence awarded a contract for the supply and delivery of fuel to a supplier using different evaluation criteria from those stipulated in the original request for quotations, which specified that the contract would be awarded to the bidder with the lower price. The mode of transport was also changed after the award, causing a further price increase. The non-compliance caused a material financial loss of R2,6 million due to the higher price being paid for fuel.

- The Property Management Trading Entity did not follow competitive bidding processes to appoint contractors and a consultant for the Beitbridge border post infrastructure project in March 2020. This is likely to result in material financial losses, as the entity did not secure market-related prices.

No or limited benefit received for money spent and properties owned

For auditees to get the maximum benefit from contracts with suppliers, the decisions they make must be economical and in their own best interest.

The public works sector rents out properties that it owns and that it leases from landlords to client service departments and other lessees for office and residential accommodation, respectively. At 31 March 2022, the sector had 1 510 unused properties because client departments opted not to extend their leases for these properties due to the lack of preventative maintenance (as discussed in the previous section).

Some auditees received limited benefit for money spent, which resulted in (or is likely to result in) financial losses because the goods and services were not required and should not have been acquired. We notified the accounting officers and authorities of these material irregularities.

Example of lease payments on unoccupied government properties

From 2015-16 to 2019-20, the Department of Defence made R108,3 million in lease payments for unoccupied office buildings.

Example of unused government properties

From 2008, the local municipality responsible for Bethulie, a small town in the Free State, used a property as a clinic before surrendering it to the Free State Department of Public Works and Infrastructure due to a lack of maintenance. The latter department concluded a lease agreement with the Free State Department of Social Development, located in the same geographical area, for a property from a private landlord at an annual cost of R392 050, increasing by 7,5% per year. If the public works department had adequately maintained the Bethulie office, it could have been the preferred building for the social development department, but the public works department had no budget available to maintain the building.

Example of software licences in excess

The State Information Technology Agency paid a service provider for 31 898 software licences – significantly more than the 2 500 licences deployed by the agency and its clients.

Auditees did not conclude contracts in their own best interest, resulting in expenditure that could have been avoided. Of the 125 software contracts we reviewed at 102 auditees, we found that for close to 20% of these contracts, the auditees did not derive the intended value. Common weaknesses across the selected contracts include contracting for more software licences than required, contracting for professional licences instead of the cheaper limited licences that would be sufficient for users to perform their job functions, and making payments for software licences that are not used due to delayed system implementation projects. This demonstrates a lack of prudent spending.

Examples of information technology systems and software not used

- The modernisation programme of the Department of Home Affairs is significantly behind schedule, with the biggest concern being the Automated Biometric Identification System project. At 31 March 2022, phase 1 of the project was three years and four months behind schedule and R294 million of the total budget of R475 million was disclosed as irregular expenditure, with R12,8 million being disclosed as irregular expenditure for 2021-22.

- In February 2017, the Department of Employment and Labour entered into a R434,23 million contract to implement SAP S/4HANA enterprise resource planning software. Due to inadequate needs analysis and project monitoring, the department paid for licences that are not being used. The system has still not been implemented and the department has incurred fruitless and wasteful expenditure of R23,03 million.

- The Integrated Financial Management System project was intended to replace ageing financial transversal systems, namely BAS, Persal and Logis. Cabinet approved the project, which was intended to commence in 2005 with an estimated timeline of seven years. Despite having an approved programme plan, programme milestones were delayed because of challenges in the appointment of a suitable service provider to perform implementation of already procured licences, which may lead to further delays in implementing the programme, currently scheduled for 31 March 2024. In 2021-22, the National Treasury disclosed R68,23 million for technical support and maintenance. There is, however, an ongoing dispute with the National Treasury regarding the non-disclosure of this expenditure as fruitless and wasteful expenditure. The dispute had not yet been resolved at the time of this report.

Infrastructure not maintained and secured

Government properties are not always safeguarded due to budget constraints. An estimated 51 properties in the public works sector were vandalised across all provincial departments, with approximately half of the vandalised properties located in the Northern Cape. The properties will now need to be extensively refurbished at additional cost to be fit for future occupancy.

Examples of vandalism to government properties

- Eleven schools in the Northern Cape were reported to have been set alight or vandalised between 2014 and 2022, resulting in learners having to be accommodated at other schools.

- A property in Cape Town was previously leased to a global fishing company that terminated the lease agreement and handed over the property to the Department of Public Works and Infrastructure in March 2021 due to a fall in production. The property was vandalised because there was no asset management or security in place, and its current poor condition represents not only a danger to the community, but also a loss of potential revenue.

Uneconomical practices for leasing of properties

Because of an overreliance on month-to-month leases, the public works sector paid rental rates that were higher than the average market rate.

Although the number of month-to-month leases across the sector has decreased due to short-term contracts (one to two years) being negotiated with landlords, this did not result in savings. When landlords refused to renegotiate rentals for month-to-month leases, the public works and infrastructure minister decided to stop payment. However, this led to a number of auditees being locked out of their offices and a court order instructing payments to be made.

Lease rates were already higher than the market price and contract terms with landlords were not concluded to the benefit of tenants, with high annual increases. Converting from month-to-month leases to contracts of between one to two years presented an ideal opportunity to renegotiate the terms of the lease to be in line with market prices. Instances of savings were noted after renegotiating lease terms, such as the Armscor building occupied by the Department of Defence, which resulted in an annual saving of R32 million and R182 million over the five-year lease term.

Examples of overreliance on month-to-month leases and higher-than-market rates paid

- The Department of Home Affairs leased and occupied the Hallmark building from November 2009 to October 2017 at a rate of R77 per square metre, with an annual increase of 10%. From November 2017 when the lease expired until February 2022, the department was on a month-to-month lease with the same terms and conditions as the original lease agreement. In an attempt to reduce month-to-month leases, in March 2022 the department extended the lease agreement by one year on the same lease terms. On 1 March 2022, the rate per square metre had risen to R241, compared to the average market rate of R60 per square metre for a similar building in the same area. This means the department has paid (and lost) approximately R44,6 million above the market rate for the year.

- The Johannesburg regional office of the Property Management Trading Entity has occupied the Mineralia building on a month-to-month lease for nine years. On 31 March 2022, the rate increased to R206 per square metre with a 10% annual increase. The Department of Mineral Resources and Energy, which is in the same building with similar lease terms, asked to move due to the high cost of the lease. It then followed a competitive process to lease new office space within a 500-metre radius and entered into a lease agreement at a rate of R95 per square metre with an annual increase of 6%, resulting in a significant saving. The Property Management Trading Entity did not renegotiate its lease term to be in line with market rates and continues to pay R11 million per year more than it should.

Inadequate needs analysis and project management resulting in escalating costs due to delays and standing time

For projects to be delivered on time, within budget and at the required quality, requires proper needs assessment, project planning and project management processes.

Poor planning and project management resulted in suppliers being paid for standing time on projects, as well as increased completion costs due to delays and projects being cancelled after substantial payments had already been made.

Examples of standing-time payments to contractors and delays in project completion with escalating costs

- The KwaZulu-Natal Department of Transport paid a contractor R2,35 million for standing time after suspending a project that was due to start on 8 June 2019 because it did not have the required approved environmental management programme at that date.

- The Free State Department of Human Settlements paid a supplier for standing time during the covid-19 lockdown period, even though it had no contractual obligation to do so.

- Construction of a magistrate court project with an initial budget of R94,74 million was delayed by more than six years due to late site handover to contractors, delays in issuing working drawings, and extension of time due to civil unrest. This resulted in overspending of R23,72 million. To date, 12 extension-of-time claims amounting to R15,88 million (654 days) have been submitted to the Property Management Trading Entity.

Example of delays in project completion with escalating costs

The Malebogo Primary School in the Free State was only partially completed by 31 March 2022, approximately five years after the planned practical completion. During our site visit on 21 June 2022, we noted that some deliverables, such as the hall, were still outstanding as the contractor prioritised completing the learning and teaching facilities. These prolonged delays exposed the Department of Basic Education to cost escalations and/or cost overruns as the project cost rose by R23,97 million (54%) from the initial cost of R67,97 million.

Examples of suppliers not delivering

- The project management team at Dinizulu Senior Secondary School in the Eastern Cape did not swiftly and effectively address project quality issues, enforce quality control, or address the contractor’s poor workmanship. This project was also delayed by 40 months.

- At Batlharo Tlhaping Secondary School in the Northern Cape, the contractor’s work was certified as being practically completed and fit for use even though there was no electrical connection to the main supply. The value of the electrical installations was R2,38 million.

For years we have highlighted these areas of vulnerability in terms of financial losses and prudent spending, but the shortcomings indicated above clearly show that government is not getting a good return on the investments made.

Eroding of funds and future obligations

The funds budgeted by government for service delivery activities are eroded by claims made against departments, and by departments overspending their budgets and being in poor financial health. Ailing institutions place further pressure on government finances, such as failing state-owned enterprises needing bailouts and through potential future obligations as a result of guarantees.

Claims against departments

Claims are made against departments through litigation for compensation as a result of a loss caused by the department. The most common type of claim is medico-legal claims (in other words, medical negligence and malpractice claims) against provincial health departments. Departments do not normally budget for such claims; and those that do, often do not budget enough. The measures implemented by departments to manage and defend medico-legal claims are also flawed. As a result, all successful claims will be paid from funds earmarked for service delivery, further eroding departments’ ability to be financially sustainable and to deliver on their service delivery commitments.

In 2021-22, the estimated settlement value of claims against departments totalled R153,64 billion. This amount represents claims that have not yet been settled (by court order or mutually between the parties). In accordance with the Modified Cash Standard, departments report an estimated value of the claim based on the most likely outcome of the process. As in the previous year, the provincial health departments accounted for the largest portion of this amount (67%).

Sixty departments (40%) had claims against them with an estimated settlement value that exceeded 10% of their budget for the following year. If paid out in 2022-23, these claims would use up more than 10% of these departments’ budgets meant for other strategic priorities, including service delivery.

The financial health of the health sector has been under immense pressure for years because of limited budget and poor financial management. This situation is made worse by medical negligence and malpractice claims, with the sector having paid R855,66 million in claims in 2021-22. Total claims against the sector currently stand at R103,64 billion.

In our previous general reports, we consistently highlighted the need for the health sector to pay specific attention to medical record keeping, because claims often cannot be successfully defended without these records – and then need to be paid out. Departments are also ordered to pay interest on claims not paid out to beneficiaries by the time ordered by the court. This interest is then a further financial loss for departments.

In 2015, the health minister approved a strategy to address the increasing medico-legal claims. We audited the implementation of the strategy and found the following:

- In 67% of healthcare facilities inspected, administrative staff shortages affected medical record keeping because vacant posts could not be filled due to financial constraints. Insufficient storage space increased the risk of being unable to access medical records when they were required to defend against claims. The facilities did not record patient safety incidents on registers, which also contained errors, because staff did not adhere to policies and procedures when recording the incidents.

- The national litigation strategy required provincial departments to take early action upon receipt of letters of demand of medico-legal claims to ensure prompt action and early resolution. Policies and procedures were developed across all nine provinces, but there were shortcomings in the measures implemented by management for medico-legal claims.

- The national litigation strategy required a uniform, national reporting system of adverse events related to patient safety and that district specialist teams must be empowered to promote and enforce patient safety. However, patient safety incidents were not effectively managed and were not always recorded on the monitoring system in accordance with the relevant policies and procedures.

- The Department of Health entered into a three-year contract with a service provider to develop a case management system to keep records of medico-legal claims. The expected completion date for the project was March 2020, but by September 2022 the system had only been rolled out to four of the eight provinces (excluding the Western Cape) and was only being used in one province. Those with access to the system were seeing very little benefit because they were not ready and willing to use it and the system did not support the objective of managing medico-legal claims. The system needs further development because no feasibility study was conducted before it was implemented.

- A shortages of medico-legal officers in six provinces (Eastern Cape, Free State, Gauteng, Limpopo, Mpumalanga and Northern Cape) and a lack of medical expertise in two provinces (Free State and Mpumalanga) contributed to delays in finalising medico-legal claims.

If the health sector challenges relating to record keeping, staff shortages, and policies and legal frameworks are not addressed, they will have a detrimental long-term effect on the sector’s ability to deliver swift, good-quality healthcare services.

Overspending of budgets and poor financial health

When departments overspend their budgets, they disclose this as unauthorised expenditure. In 2021-22, 9% of departments incurred unauthorised expenditure totalling R2,3 billion, of which 97% was incurred by key service delivery portfolios. Almost all of the unauthorised expenditure related to budget overspending. If this type of expenditure is condoned, it means that the department needs to either appropriate more money or absorb the overspent amount, which erodes the budget for following years.

Departments have to submit their budget vote to parliamentary committee hearings to be approved. After the finance minister presents the budget, the committee asks the department what it plans to achieve with its budget. The committee can also check whether the department kept the promises it made for the previous year and whether it spent taxpayers’ money properly. Unlike departments, public entities do not have a separate vote and hence their overspending is disclosed as irregular expenditure. Seven public entities disclosed irregular expenditure incurred as a result of overspending.

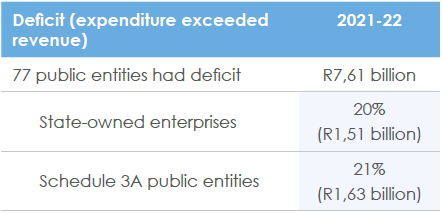

When an auditee has a deficit at year-end, it means that it did not have sufficient revenue to cover all its expenses – the auditee thus ended the financial year in the red. This most often means that the following year’s revenue is used to cover the shortfall. Overall, public entities (including state-owned enterprises) ended 2021-22 with deficits totalling R7,61 billion. Of this amount, over 40% was incurred by state-owned enterprises and schedule 3A public entities that are funded through revenue such as levies and taxes and will either need additional funding or will need to use their reserves.

The public entity with the highest deficit over the past few years is the Road Accident Fund, but the audit of the fund had not been completed by 15 September 2022 and thus its information is not included in this report.

The major contributors to the deficit of R7,61 billion were:

- Roads Agency Limpopo – R1,73 billion (23%)

- Gautrain Management Agency – R0,80 billion (10%)

- Airports Company South Africa – R0,66 billion (9%)

- Petroleum Oil and Gas Corporation – R0,39 billion (5%)

- Autopax – R0,37 billion (5%)

Departments prepare their financial statements based on the modified cash basis of accounting. This means that the amounts disclosed in the financial statements only include what was actually paid during the year and do not include accruals (the liabilities for unpaid expenses) at year-end. While this is common for government accounting, it does not give a complete view of a department’s year-end financial position.

We believe it is important for management to understand the state of a department’s finances, which may not be easily seen from its financial statements. This is why, every year, we reconstruct the financial statements at year-end to take these unpaid liabilities into account. This allows us to assess and report to management whether the surpluses reported are the true state of affairs and whether the departments have technically been using the next year’s budget because of overcommitments in a particular year.

Based on these reconstructed financial statements, a picture emerges of deficits and cash shortfalls at departments that could not operate within their budgets.

More than 60% of departments did not have enough funds to settle all their liabilities at year-end – in other words, they had cash shortfalls. This means that these departments started the 2022-23 financial year with part of their budget effectively pre-spent.

The departments that incurred the highest percentages in this regard were:

- Department of Social Development (national) 3 539% (cash shortfall: R15,171 billion; following year’s operating budget: R428,70 million)

Reason: Some April 2020 grants were paid in March 2020 following the announcement of the covid-19 lockdown in March 2020, resulting in a R15 billion overpayment in grants for the 2019-20 financial year as well as a bank overdraft of R16,15 billion. The shortfall has not been funded from the 2020-21 and 2021-22 allocation and will need a resolution from the Standing Committee on Public Accounts to regularise the unauthorised expenditure.

- KwaZulu-Natal Department of Public Works 213% (cash shortfall: R582,46 million; following year’s operating budget: R273,01 million)

Reason: The department uses an overdraft facility that was approved by the provincial treasury to procure on behalf of other client departments, and its cash reserves are thus always negative. The client departments are taking a long time to repay some of their outstanding debts, which is also a contributing factor.

- Free State Office of the Premier 163% (cash shortfall: R205,39 million; following year’s operating budget: R126,14 million)

Reason: Mainly attributable to insufficient funds to repay voted funds that have to be surrendered back to the provincial revenue fund, largely due to underspending on goods and services as a result of the covid-19 pandemic and unclaimed funds for the public information platform.

Departments get most of their revenue through budgeted funds from government. Some departments also generate revenue, which they need to collect. Any surpluses at year-end are paid back into the National Revenue Fund or into provincial revenue funds, which then fund departments’ budgets in the following year.

Departments continued to struggle to collect the debt owed to them, such as patient fees owed to health departments, as can be seen in long debt-collection periods and the significant portion of debt that is deemed irrecoverable. If a department does not collect the debt owed to it, this affects not only its operations, but also the funds available for future government initiatives.

Most public entities are self-funded, which means they need to ensure that all the goods or services they sell or the levies and taxes they are responsible for collecting, are billed and the debt is collected. However, public entities also struggled with debt collection, as can be seen from their average debt-collection period. Some of these entities also did not bill the revenue.

Example of revenue not billed

According to the policy of the National Student Financial Aid Scheme, interest on student loans is supposed to be charged one year after students graduate or leave the tertiary institution.

The scheme did not have up-to-date information on students’ status, resulting in loan recipients being recognised as students for many years after they had stopped studying, without interest being charged on their loans. This non-compliance is likely to result in a material financial loss of just over R1 billion if the interest is not recovered.

The financial position of 23 public entities is so dire that there is significant doubt that they will be able to continue operating as a going concern in the near future. This effectively means that these public entities do not have enough revenue to cover their expenditure and that they owe more money than they have. Many of these public entities have been in this dire financial position multiple times over the past five years.

State-owned enterprises

Government has made it clear that it intends to reduce the continual demands of state-owned enterprises on South Africa’s limited public resources. Most state-owned enterprises are still battling with going concern challenges, with three having disclosed material uncertainties about whether they would be able to continue operating (Independent Development Trust, Land and Agricultural Development Bank of South Africa, and South African Broadcasting Corporation) while two (South African Post Office and South African Nuclear Energy Corporation) received modified audit opinions because they did not have sufficient evidence to show that they would be able to continue operating. The South African Post Office, the South African Nuclear Energy Corporation and the South African Broadcasting Corporation need their respective accounting authorities to intervene, with the support of the shareholders. Their continued going concern challenges, coupled with successive losses, indicate that their turnaround plans either are not effective or have not been fully implemented.

State-owned enterprises should not rely on government bailouts as they are expected to implement sustainable turnaround plans that will ensure the creation of public value. Government provided financial guarantees of over R420 billion over several years to these entities. The total government exposure relating to these guarantees is over R328 billion (exposure means that the entities have used the guarantees to obtain loans from lenders). Eskom is the single biggest fiscal risk to the National Revenue Fund, accounting for over 80% of government guarantees to state-owned enterprises.

When the state grants a guarantee, it essentially takes responsibility for repaying a loan if the state-owned enterprise defaults. If these entities do default on their loans, the guarantees can be a direct charge to the National Revenue Fund. The fund keeps record of all guarantees issued and government’s total exposure. In certain circumstances, guarantees are required, but the entity should ensure that it honours the conditions of the guarantee and that it becomes sustainable so that further guarantees will not be necessary.

Slow progress has been made in the implementation of key reforms announced by government, such as the Shareholder Management Bill and the funding criteria for state-owned enterprises. There is an urgent need to finalise these reforms to ensure policy certainty and empowerment of state-owned enterprises to deliver on their developmental mandates.

Financial management

Credible financial statements are crucial for enabling accountability and transparency, but many auditees are failing in this area. Auditees are required by legislation to submit their financial statements on time. The goal of this requirement is to ensure that auditees account for their financial affairs when this information is still relevant to stakeholders for decision making and oversight.

Parliamentary committees and legislatures use financial statements to hold accounting officers and authorities accountable and to make decisions on, for example, the allocation of the budget. For some public entities, creditors, banks and rating agencies also use the financial statements to determine the level of risk in lending money to the entity. Members of the public can further use the financial statements to see how well the departments and public entities are using the taxes they pay to provide services.

A total of 92% of auditees submitted their financial statements by the legislated date – a slight regression from 93% in the last year of the previous administration.

The table below shows the 15 public entities that had not submitted their financial statements for auditing by 15 September 2022, which was the cut-off date for inclusion in this report. Most of these public entities are state-owned enterprises.

For the past three years we have reported that the three North West provincial public entities have not submitted their financial statements. We have also informed the provincial leadership, treasury and legislature. Our audit leadership has repeatedly engaged with the boards, chief executive officers and chief financial officers of these public entities to encourage them to submit their financial statements. When all of this failed, we invoked our powers to hold the accounting authorities of these three public entities, as well of those of six others, accountable by notifying them that not submitting financial statements constitutes a material irregularity, as the delays in the accountability processes are causing substantial harm to these public entities. This lack of transparency in the use of funds and the financial position should not be tolerated.

Impact

When departments and public entities do not submit their financial statements, this negatively affects the accountability chain because the various stakeholders cannot evaluate the state of these auditees.

Credible financial statements are crucial for enabling accountability and transparency, but more than half of the auditees continue to submit poor-quality financial statements for auditing. This means that if we had not identified misstatements in these financial statements and given the auditees the chance to correct them, only 48% of auditees with completed audits would have received unqualified audit opinions, compared to the 78% that ultimately received this outcome.

A qualified audit opinion means that there were areas in the financial statements that we found to be materially misstated (meaning that there are material errors or omissions that are so significant that they affect the credibility and reliability of the financial statements). In our audit reports, we point out which areas of the financial statements cannot be trusted. In total, 76 auditees (31 departments and 45 public entities) received qualified audit opinions.

Adverse and disclaimed audit opinions are the worst opinions an auditee can receive. An adverse opinion means that the financial statements included so many material misstatements that we disagree with virtually all the amounts and disclosures. A disclaimed opinion means that those auditees could not provide us with evidence for most of the amounts and disclosures in the financial statements. Effectively, the information in financial statements with adverse or disclaimed opinions can be discarded because it is not credible. In our audit reports, we tell oversight structures and other users of the financial statements that the information cannot be trusted. In 2021-22, only the North West Development Corporation received an adverse opinion.

Over the years, we have called on national and provincial leadership and oversight to direct their efforts towards auditees that continue to receive disclaimed opinions. In 2021-22, nine public entities received disclaimed opinions. Seven of these public entities had also received disclaimed opinions in 2020-21 and six had also received this type of opinion in 2019-20. No department received a disclaimed audit opinion in 2021-22.

Basic financial management processes do not always function as they should. These include institutionalising a culture of compliance and controls, such as implementing standardised, effective accounting processes for daily and monthly accounting disciplines; ensuring proper record keeping and document control; performing independent reviews and reconciliations of account records; and ensuring that in-year reporting and monitoring (including proper project management) take place. Dealing with the consequences of poor financial management is costly and time-consuming and the results often cannot be reversed. If auditees do not implement these basic processes, it can lead to a lack of prudence and eroding of funds, placing government’s economic recovery initiatives at risk.

Economic recovery

In pursuit of the National Development Plan goals and amidst the deepening economic crisis following the covid-19 pandemic, government introduced the Economic Reconstruction and Recovery Plan for the South African economy in 2020 with the aim of stimulating equitable and inclusive growth. The plan includes a number of priority interventions such as aggressive infrastructure investment, which is a critical catalyst for creating the multiplier effect that drives economic activity. As detailed in the section on infrastructure, the success of the infrastructure programme will depend on government’s ability to urgently address the weaknesses in infrastructure delivery so that value for money is received for every rand spent.

Another key intervention includes employment initiatives such as Presidential Employment Stimulus programmes, which aim to protect jobs and livelihoods and to support meaningful work while the labour market recovers from the covid-19 pandemic. We have identified risks of funding being received late, which affected the implementation of some projects, resulting in the planned targets for job creation not being achieved for some initiatives. Work opportunities were also mostly short term and related to unskilled labour, which does not result in sustainable job opportunities. Going forward, our audits will have an increased focus on these initiatives so that we can provide insights on how they have been implemented.

It is increasingly important that the identified risks are addressed through good financial management practices and improved governance. Auditees should be intentional about the implementation of set programmes; hence, these reforms should be implemented with a sense of urgency to ensure value for money and return on investment. The more pressure there is on the fiscus, the less money is available for service delivery which negatively affects the lives of the people of South Africa.

Other pages in this section:

Other pages in this section: