State of national and provincial government

GOVERNANCE AND ACCOUNTABILITY

The continued increase in the irregular expenditure balance that is not being dealt with, coupled with the lack of action on potential fraud and corruption and the continued disregard for our findings and recommendations at some auditees, clearly show weakness in governance and accountability at national and provincial auditees – further hampering their ability to deliver services. As highlighted in the preceding sections, we used the material irregularity process where accounting officers and authorities did not take action to deal appropriately with irregularities identified.

On this website, we also highlight the roleplayers in the accountability ecosystem responsible for governance. Over the past few years, we have called for a more responsive system of governance and made continued calls for accountability.

Accountability is two-fold:

- Firstly, those who take actions or make decisions must take responsibility for these actions and decisions.

- Secondly, those who do wrong (transgress), do nothing (fail to act) or perform poorly should face consequences.

In this section, we examine:

- the status of non-compliance with procurement legislation and resultant irregular expenditure, and the lack of consequences that leads to an environment in which further non-compliance is likely

- the vulnerability of government systems to cybersecurity attacks because of weak information technology governance and security controls

- the need to pay specific attention to governance and oversight of state-owned enterprises because of the impact they have on government’s financial health.

Procurement – consequence management

Fair and competitive procurement processes enable government to get the best value for the limited funds available and give suppliers fair and equitable access to government business. Such requirements are not only standard financial management practices, they are also included in the legislation that makes accounting officers and authorities responsible for ensuring that the required processes and controls are implemented.

The procurement process is also where the risk of fraud is highest, which is why we pay particular attention to procurement and contract management during our audits.

We continued to identify and report findings on compliance with procurement and contract management legislation at auditees. We identified findings across all key service delivery portfolios and 16 state-owned enterprises.

The irregular expenditure disclosed in 2021-22 was R51,22 billion. It is significantly less than the R136,67 billion disclosed in the previous year, but the R77,49 billion irregular expenditure incurred by the National Student Financial Aid Scheme in that year was an anomaly.

In total, R40,16 billion of the R51,22 billion was expenditure incurred in 2021-22 (representing 2% of the R2,58 trillion expenditure budget) and R11,06 billion was prior year expenditure that was only identified and disclosed in 2021-22.

The total irregular expenditure could be even higher, as 25% of auditees did not report all irregular expenditure that should have been reported in their financial statements. In some cases, the amount of irregular expenditure reported was incorrect. We also could not audit contracts worth R2,53 billion because of missing or incomplete information.

As part of our audits, and to assist oversight and portfolio committees with areas on which to focus their attention, we assessed the impact of irregular expenditure. We identified that R38,68 billion arose from breaches of legislation, which requires that procurement be fair, equitable, transparent, competitive and cost-effective. This resulted in goods and services being acquired at unreasonable prices because auditees either did not adequately test market prices or did not choose the most

cost-effective options. Government’s socioeconomic objectives, such as advancing previously disadvantaged individuals and small businesses, were also not achieved. This could lead to exposure to litigation arising from breaches of procurement and, as a result, funds intended for service delivery might be shifted to pay legal fees.

Instituting consequences against officials responsible for non-compliance helps auditees to recover the losses that those officials incurred and to deter other officials from contravening legislation. In this way, auditees demonstrate their commitment to prudent financial management practices.

However, 44% of auditees did not comply with legislation on implementing consequences. At 35% of auditees, this non-compliance was material. As a result, the year-end balances of these types of unwanted expenditure continue to grow. A culture of consequence management has not materialised because the right tone has not been set to encourage a behavioural change at the highest levels.

The balances of unauthorised, irregular, and fruitless and wasteful expenditure remain high at R461,05 billion due to the slow pace of investigations. Taking irregular expenditure as an example, by the end of the 2021-22 financial year very little had been done about the previous year’s closing balance of R408,52 billion.

The first step that auditees must take is to investigate the non-compliance – why did it happen; who is responsible; was money lost; and, if it was, can that money be recovered? Almost a third of auditees did not perform these investigations, and where action was taken, it was mostly to condone or write off the irregular expenditure.

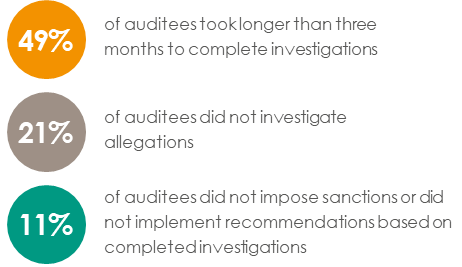

Where there have been allegations of financial and supply chain misconduct and fraud, accountability should also come into play. We audited 99 auditees at which allegations of fraud and misconduct were flagged to management to see if this was the case, and found the following:

Every year, we also report indicators of possible fraud or improper conduct in supply chain management processes and recommend that management further investigate these matters.

Status of auditees’ investigations into fraud or improper conduct of supply chain management processes

Cybersecurity

Government departments and entities use information systems to process critical business transactions and reports on operational and financial performance. Information security measures are therefore critical to ensure that government information systems are not vulnerable to cyberattacks and to prevent people from performing system activities that are unauthorised so as to limit fraud incidents.

Our role is to assess the control environment supporting these systems to determine if there are any risks of unauthorised access to the systems and data, whether we can rely on the controls for audit purposes, and whether government is deriving value from its investment in information technology.

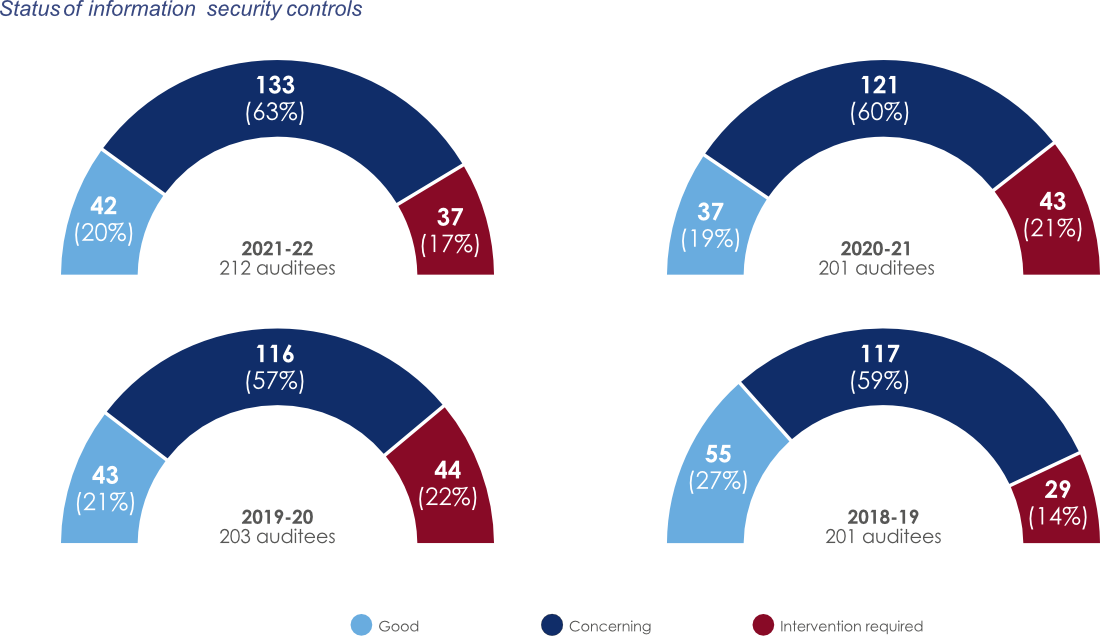

We identified that 80% of auditees had ineffective security controls. This area has shown a negligible movement over the past year and since the end of the previous administration’s term.

The National Cybersecurity Policy Framework was gazetted in 2015 and outlines policy guidelines related to cybersecurity in South Africa, requiring government to develop detailed cybersecurity policies and strategies. Neither the State Security Agency, nor any other security and justice related departments, have made much progress in achieving the objectives contained in the framework. This was due to limited oversight of the framework, its complexity and a lack of consequence management because there were no implementation timelines. This has impaired government’s ability to coordinate cybersecurity efforts and inherently affected its cybersecurity spend.

Departments and entities had no choice but to use the State Information Technology Agency’s unsupported and vulnerable infrastructure to access their financial systems, which exposed the government to cyberthreats.

There has been an increased trend of high-profile cybersecurity failures. Hackers have successfully exploited the security weaknesses at some of the auditees that we rated as weak in this area. This resulted in some key government services not being available for a prolonged period and, in some cases, hackers demanding ransom or significant fraud being perpetuated. Among the auditees most recently affected are the Department of Justice and Constitutional Development, Transnet and Postbank.

The prevailing root cause of information technology security weaknesses is poor information technology governance processes. We identified that 144 auditees (68%) had ineffective information technology governance processes, and noted the following deficiencies at many auditees:

- Although auditees had adequate, and in some cases well-defined, information technology governance frameworks, these were not implemented or operating effectively.

- Where information technology steering committees had been established, they were not operating effectively. Either these committees did not have the required level of representation or they did not meet regularly to discharge their oversight responsibilities.

- Information technology budgets and plans were not well defined or monitored to ensure that they delivered the expected value and benefits.

- Service level agreements with third parties were lacking or, where they existed, services were not monitored.

- Information technology risks were not well articulated in risk registers and management did not monitor action plans to mitigate the risk. In some cases, internal auditors did not perform required information technology risk assessments, especially around key processes and significant projects.

The cybersecurity and information technology environment at government departments and public entities is weak because accounting officers and authorities have not discharged their responsibility to effectively manage and implement these governance processes over a number of years. A cybersecurity culture shift is required to mitigate risks and improve controls as system automation continues to increase. We will continue to focus and report on cybersecurity risk in future.

Governance and oversight of state-owned enterprises

The performance by state-owned enterprises is key to the economy but most state-owned enterprises are in a dire state, receive poor audit outcomes and are struggling to deliver against their legislated mandates. Many are in financial distress with collapsing infrastructure that weakens their ability to deliver key services. All of this has a significant impact on the day-to-day experiences of businesses and the lived reality of the people of South Africa.

The overall control environment within state-owned enterprises also remains weak in the areas of financial reporting, performance reporting, and compliance with legislation. The key contributors to the unfavourable audit outcomes include poor governance processes, instability at senior management and executive levels, lack of consequence management, ineffective strategic planning and monitoring, and lack of regular reconciliation, review and reporting.

There is slow progress in implementing the key reforms aimed at strengthening governance at state-owned enterprises, such as finalising the Shareholder Management Bill and clarifying the as yet unfinalised funding criteria for state-owned enterprises, creating policy uncertainty in the state-owned enterprise environment.

In June 2021, the state announced that it plans to sell 51% of South African Airways to a private consortium and retain a minority stake, while Eskom permitted independent power producers to increase self-generation from 1 MW to 100 MW without needing a licence. However, the persistent financial and operational challenges confronting state-owned enterprises cast doubt on their ability to survive without continued financial support from government – when they should be paying dividends to government.

To improve the governance of state-owned enterprises, we made detailed recommendations in their management reports, which can only succeed if:

- key reforms are implemented and the entities have sound internal control environments and effective governance structures and processes in place

- competent people of integrity are appointed to boards and executive positions via transparent and robust processes

- lessons are learnt from the various investigative commissions of enquiry and their recommendations are implemented.

Other pages in this section:

Other pages in this section: