Material irregularities

Material irregularities explained

As a chapter 9 institution, the Auditor-General of South Africa (AGSA) has its mandate and functions outlined in the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa. The Public Audit Act (PAA), which further defines the organisation’s functions, and its regulations have been shaped to support the process of fair, transparent and legally sound administrative justice by giving accounting officers ample opportunity to fulfil their duties, rectify any breaches and compromises in the system of internal controls, and address any financial management failures.

Download our latest material irregularity (MI) report

In this report, we share details on material irregularities identified across all spheres of government and their status at 30 September 2022. The report also includes information on the actions being taken to resolve the MIs – by the accounting officer or authority, or through the use of our expanded powers.

Why was the AGSA’s mandate expanded?

Ideally, the preventative controls in government should be so effective that it would be difficult to sidestep or manipulate them, and it should be easy to detect and deal with any attempts to do so. And, if someone actually successfully misuses public money, the accounting officers or authorities concerned would act quickly to recover the money and take the necessary action.

Unfortunately, this isn’t always what happens.

In 2016, concerned by the growing extent of unauthorised, irregular, and fruitless and wasteful expenditure the AGSA reported every year at all tiers of government, the standing committee on the auditor-general (Scoag) – the multiparty parliamentary committee that oversees the AGSA – initiated the process to expand our mandate beyond just auditing and reporting.

The members of this committee, later fully backed by the National Assembly, the National Council of Provinces and the President of the Republic, felt that expanding our mandate would go a long way to support other existing pieces of legislation, such as the Municipal Finance Management Act (MFMA) and the Public Finance Management Act (PFMA), that aim to ensure good governance and clean administration in the public sector. Both Acts contain extensive guidance on what the law requires accounting officers and authorities to do, and even outline the consequences for financial misconduct, including the responsibility to quantify and recover money due to the state.

In 2018, the president signed the Public Audit Amendment Act into to law to enhance the AGSA’s powers, expanding our mandate to go beyond auditing and reporting in an effort to strengthen accountability mechanisms. These amendments, which provide valuable instruments for implementing effective consequence management and taking remedial action, centre on the concept of a material irregularity (MI) and came into effect on 1 April 2019.

Evolution of the Public Audit Act

The functions of the AGSA are regulated through Acts passed in parliament. This is how they have evolved over the years.

What does this expanded mandate mean?

Our expanded mandate did not change the role and responsibilities of the municipal managers or the oversight and monitoring roles of the mayor and the council to prevent and deal with irregularities. Through the material irregularity process, we strengthen them in this role.

For example, accounting officers and authorities are responsible for preventing irregularities and acting when they do happen. We only use our expanded powers when we have detected and reported on a material irregularity and no action has been taken.

Ultimately, the amendments were meant to establish a complementary enforcement mechanism to strengthen public sector financial and performance management so that these material irregularities can be prevented, or can be dealt with appropriately if they do occur.

The overall aim of our expanded mandate is to:

- promote better accountability

- improve the protection of resources

- enhance public sector performance and encourage an ethical culture

- strengthen public sector institutions to better serve citizens.

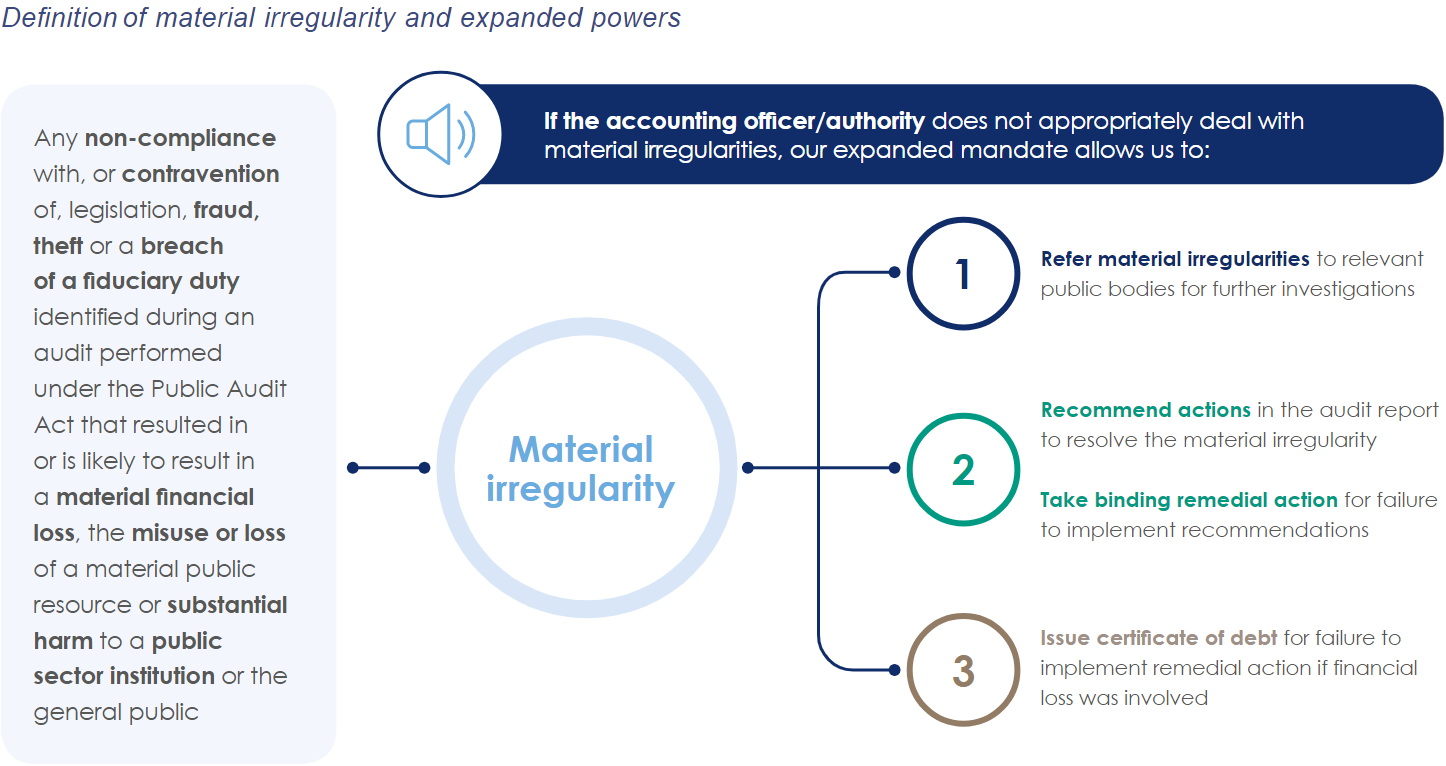

What is a material irregularity (MI)?

What do these terms mean?

Referral

The auditor-general may refer a suspected material irregularity to a public body with a mandate and powers that are suitable to investigate it, such as the public protector, the Special Investigating Unit and the Hawks.

The public body would then deal with the matter within its own legal mandate and take appropriate action where necessary.

Recommendations

The auditor-general may make recommendations in the audit report on how a material irregularity should be addressed, and give a specific deadline for the recommendations to be implemented.

Remedial action

The auditor-general may take binding remedial action if the auditee does not implement the recommendations by that date. If the material irregularity involves a financial loss, the auditor-general must also direct the accounting officer or authority to determine how much was lost and recover the amount from the responsible person or people.

Certificate of debt

If the accounting officer or authority does NOT implement the remedial action, including determining and recovering a financial loss, the auditor-general must issue a certificate of debt in the name of that accounting officer or the members of that accounting authority.

The relevant executive authority (such as a minister or a member of the executive council) must then recover the loss from the accounting officer or authority.

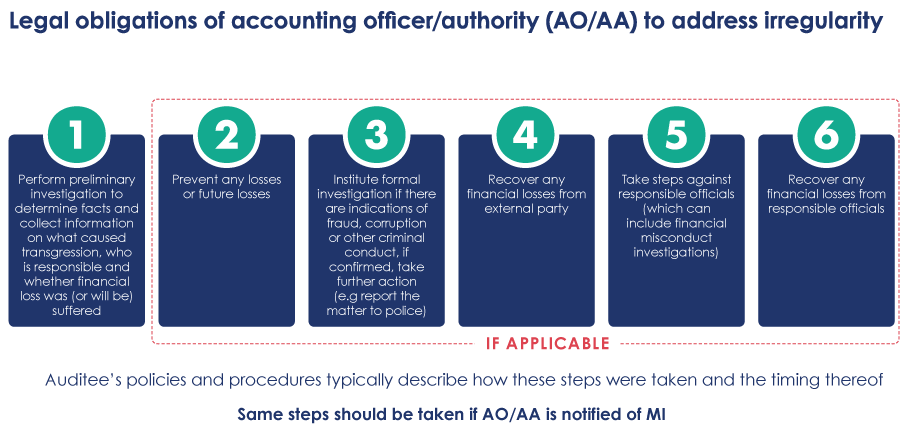

Who is responsible for resolving a material irregularity?

Accounting officers and authorities are legally required to address any irregularity (non-compliance, fraud, theft, breach of fiduciary duty) that they are aware of, and a material irregularity is no different. Typically, the legislation, Treasury Regulations and National Treasury instruction notes would prescribe the following steps (although the auditee’s policies and procedures would describe how and when these steps should be taken). The same steps should be taken in the case of a material irregularity.

Process from identifying material irregularity to issuing certificate of debt

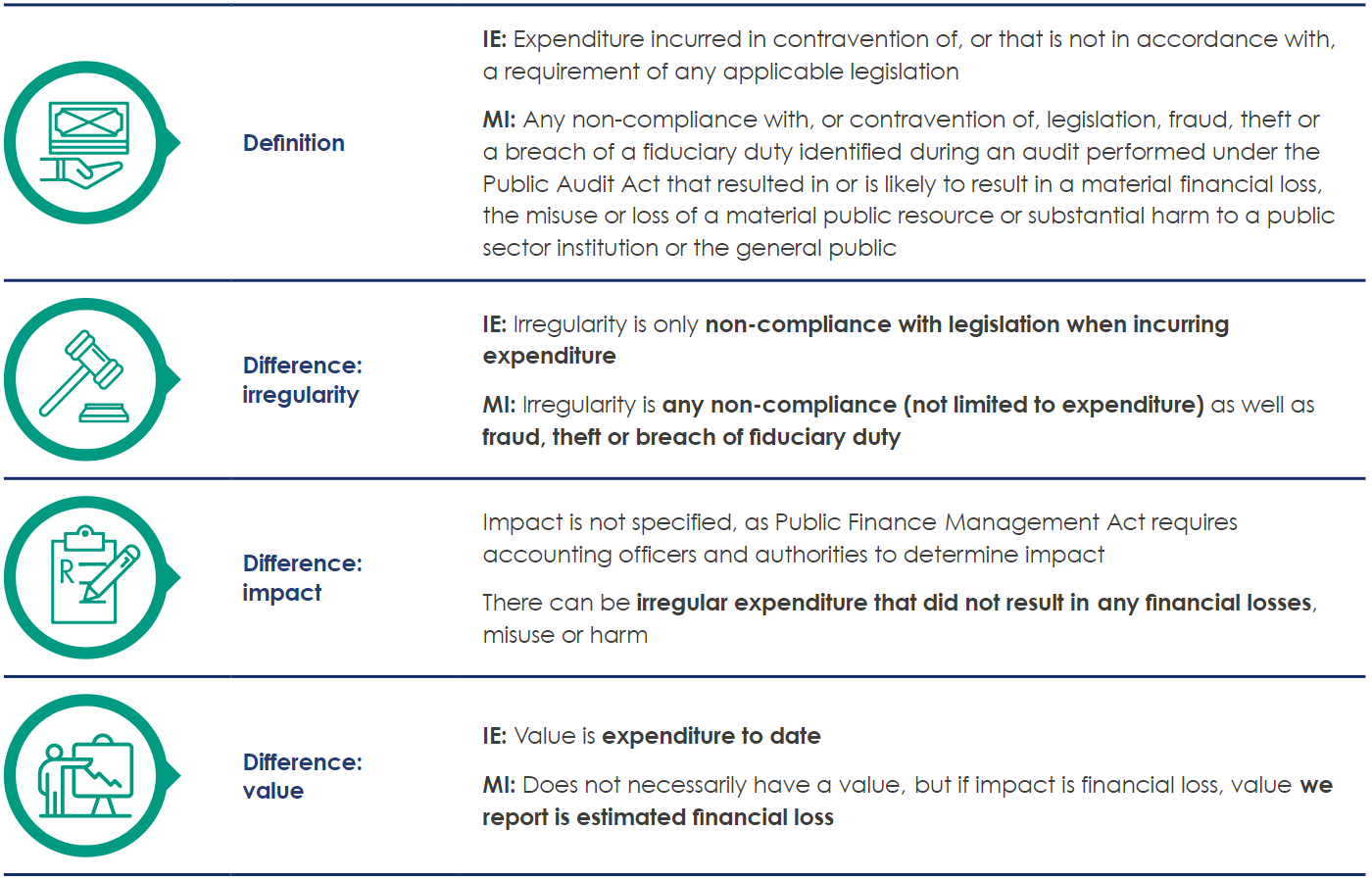

How does irregular expenditure (IE) differ from material irregularity (MI)?

Example of irregular expenditure versus material irregularity

If a department paid R20 million on a contract, but it could have gotten the same service for R18 million, then the value of the material irregularity would be R2 million (money that was spent but shouldn’t have been), while the irregular expenditure would be the entire R20 million (all the money that was spent irregularly).

Nature and value

The main difference between irregular expenditure and material irregularities are in nature and value.

Nature

Based on the definition, a material irregularity needs to pass two gates: there needs to be an irregularity (which is the non-compliance, fraud, theft or breach) and an impact (which is the loss, misuse or harm).

Irregular expenditure, on the other hand, only needs to pass the first gate –irregularity. It also only applies when money is spent.

Value

The other main difference between irregular expenditure and material irregularity is that the value of the material irregularity is the financial loss, while the value of the irregular expenditure is the total amount spent.

Other pages in this section:

Other pages in this section: